Archive for the ‘Investor Behavior’ Category

My friend Carl Richards made an interesting observation in his last post:

Just when we need something to zig, they all zagged together!

Some people draw the conclusion that diversification no longer works. I strongly disagree.

Some people draw the conclusion that diversification no longer works. I strongly disagree.

In the mind of an investor

Posted on: August 31, 2009

Found this chart on digg.com … don’t know who to give credit to. Whoever drew this is brilliant.

Investors don’t need outside help to hurt themselves. I’ve been writing about how ignoring conflict of interest, hidden fees, and not taking the necessary time to do due diligence costs investors a great deal of money. Today, I’m going to show you another way they self-inflict pain, and what to do about it.

Let’s imagine you’re in your car. Your vehicle is traveling at 60 mph. How can you, as a passenger, only be going 30 mph? You can’t. It’s an impossibility. Nevertheless, it happens in the financial world all the time.

How Madoff did it

Posted on: July 3, 2009

This week, Bernie Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison by New York District Judge, Denny Chin. With the trial now over, Madoff’s victims are still fighting over what little is left of his fund. They want to know: Where was the SEC?

This week, Bernie Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison by New York District Judge, Denny Chin. With the trial now over, Madoff’s victims are still fighting over what little is left of his fund. They want to know: Where was the SEC?

More appropriate questions should be: How did Madoff do it? What human frailties did he exploit? How was he able to con $65 billion out of the most sophisticated members of our society? Here’s how his scam worked:

Affinity

We humans lower our guard when we believe other people are similar to us. Madoff exploited this one masterfully. Much like Charles Ponzi, who looked for his prey among Italians, Bernie Madoff focused on exclusive Jewish social clubs and Jewish foundations.

In January 2008, I wrote in my article “Recession and stock market performance” that:

Small cap value stocks are likely to outperform.

With one week left in 2008, the Russell 2000 Value Index, representing small-cap value stocks, has lost 34%. This is bad, but not as bad as the S&P 500 Index’s 41% loss and the Nasdaq 100’s 43% loss this year. The S&P 500 Index represents the largest 500 stocks in the U.S. and the Nasdaq 100 represents the largest 100 growth stocks.

Since January, I’ve heard pundits recommending large-cap stocks, tech stocks, pharmaceutical stocks, etc. Never once have I heard them recommend small-cap value stocks, which they claim are the most vulnerable in a recession.

Do I have a better crystal ball?

No, I don’t. I simply know the odds. As I wrote in “Small-cap value underperforming: a historical perspective,” the odds that small-cap stocks will outperform large-cap growth stocks on aggregate in any given year is 75%. So I can make the same “prediction” year after year and still be right about 75% of the time.

Why do most investors shun small-cap value?

According to Daniel Kahneman, father of behavioral economics, certain types of information are more accessible than others to the human mind. For instance, the concept of probability is not intuitively accessible, but descriptive words like “small,” “large,” “value” and “growth” leave instant impressions on our minds.

Another discovery of Kahneman is that humans take mental shortcuts in decision making. Confronted with the choice between large-cap growth and small-cap value, most investors eschew the hard route of calculating odds. Instead, they rely on their intuition that “large” is safer than “small” and “growth” has more potential than “value.” Thus, they “decide” to shun small-cap value stocks.

Small-cap value premium

An undesirable job has to pay more to attract job-seekers. Likewise, a shunned asset class commands a higher expected return in equilibrium. As long as small-cap value is not an intuitively attractive asset class, this return premium will continue.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

Has the market hit bottom?

Posted on: December 9, 2008

“Successful investing,” in the words of British economist John Maynard Keynes, “is anticipating the anticipations of others.” In this vein, a market hits bottom when most people think that most other people think it has hit bottom. Only then, most people start to buy stocks, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. If most people think the market should hit bottom, but they also think that most other people don’t think that, they won’t buy stocks and the market will continue to drop. So, predicting when a market will hit bottom is a mind game on a grand scale. If there are people who are good at that, I am certainly not one of them.

Prescience not needed, discipline required

Now let me ride a time machine to January 1929. Let’s say I committed to invest $100 every month in the S&P 500 index. I did not have the prescience to know that the market would crash in October and the Great Depression would follow. But if I had the discipline to carry out that investment plan over 30 years, the table below summarizes what would have happened to my investment through the worst stock market period in history.

| Year from Jan 1929 | Total invested | Portfolio value | Total dividend received | Total gain (loss) | Dividend contribution to the gain |

| 1st year | 1,300 | 1,115 | 23 | (161) | |

| 2nd year | 2,500 | 1,779 | 98 | (623) | |

| 3rd year | 3,700 | 1,737 | 230 | (1,734) | |

| 4th year | 4,900 | 2,771 | 415 | (1,714) | |

| 5th year | 6,100 | 5,547 | 629 | 76 | 100% |

| 10th year | 12,100 | 12,835 | 3,024 | 3,759 | 80.4% |

| 20th year | 24,100 | 30,786 | 13,683 | 20,369 | 67.2% |

| 30th year | 36,100 | 135,992 | 47,960 | 147,852 | 32.4% |

Data source: Professor Robert Shiller’s website

The total gain from my investment plan is the portfolio value plus total dividends received minus total money invested. As you can see, though I suffered losses in the first four years, I had a small gain in the fifth year (January 1934)! This result is not bad, considering that between1929 and 1934 were the worst years for the stock market (an 89% drop) in history.

For the first 10 years of my hypothetical investment, dividends accounted for 80.4% of the total investment gain. This means that if I had invested in high dividend stocks, I would have done even better. (Also see my newsletter article, “Dividends to the rescue in a Great Depression“.)

Here is the take-home lesson from my time travel experiment: to recover from the market crash and to survive a recession, however deep, you don’t need prophecy, just discipline and patience.

The author is president of MZ Capital, a RIA serving DC/MD/VA. Get his monthly newsletter in your mailbox or get to the directory of his past articles.

David Swensen in the press

Posted on: November 4, 2008

“Don’t give up on financial innovation” by William Watson is more about Robert Shiller’s view. David Swensen did get a cusory mention.

The Economist has a piece “All bets are off” that is highly skeptical about David Swensen’s multiple asset class approach. It argues that all asset classes were driven (higher) by two factors: low interest rate and healthy global growth.

Princeton’s endowment, managed by David Swensen’s disciple Andrew Golden, earned 5.6% in 2008 (fiscal year ended in June). The performance was attributable to “non-marketable exposures and independent return managers.”

Yale Daily News: David Swensen got a raise. Now he makes $2 million dollar a year.

David Swensen derides securities lending as “make a little, make a little, make a little, lost a lot.”

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

“This sucker could go down!”

That was what President Bush said during the recent $700 billion bailout plan meeting with congressional leaders at the White House. The market has gone down another 20% and talk of another Great Depression has filled the airwaves ever since.

If you are a listener of Jim Cramer, you would have heard his advice: Sell, sell, sell! He constantly reminds his listeners how the Dow went down 83% during the Great Depression; and never fully recovered until 1954.

Cramer forgot to account for dividends. If dividends from the Dow stocks were reinvested, then investors would have been able to recoup all losses by 1945. That’s a full nine years sooner! Think about this: what if investors held only high-dividend stocks? Would they have recovered their investments even sooner?

To find out, I examined the following four portfolios’ performance from 1929 onwards:

- Portfolio A: stocks with zero dividends.

- Portfolio B: stocks with bottom 30% dividend yields.

- Portfolio C: stocks with middle 40% dividend yields.

- Portfolio D: stocks with top 30% dividend yields.

All four portfolios peaked in August, 1929. With the exception of portfolio B, all portfolios bottomed in May, 1933. Portfolio B bottomed in June, 1933. For each of the four portfolios, the total peak-to-trough decline (drawdown) and the number months it took to recover are presented here:

| Buy at the top and hold during Great Depression | ||||

| A | B | C | D | |

| Drawdown | 89% | 86% | 85.4% | 84% |

| Months to recover | 132 | 154 | 144 | 44 |

Data source: Kenneth French Data Library

It is probably not surprising that the highest dividend-yielding portfolio D fell a little less than other portfolios. It’s striking that portfolio D recouped all losses in just three-and-a-half years – eight to nine years before other portfolios.

Why did high dividend-yield stocks performed so well?

During the Great Depression, stock prices on average fell more than 80%. Dividends fell only about 11%. (See Chart below) As Yale University professor Robert Shiller has found, historically dividend volatility was about 15% of price volatility (meaning dividend declines were a fraction of price declines in recessions.) Stable dividend payments quickly made up for losses in price.

If the price gyration makes you dizzy, focus on dividends instead. They don’t gyrate and ultimately, they will sustain your retirement.

Schedule a 2nd opinion financial review, buy my wealth mgmt books on Amazon.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

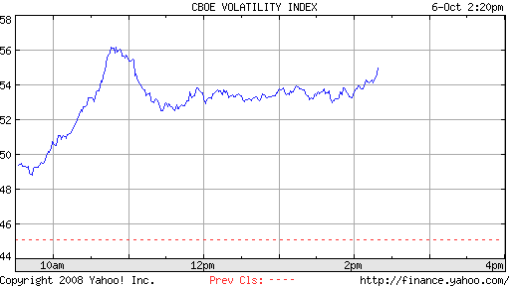

Fear (VIX) at all-time high!

Posted on: October 7, 2008

Today, the VIX index reached all-time high of 56 and closed at 52. To give a measure of how fearful investors are, in 9/11/01 during the terrorist attach the index only reached a lowly 39.

In days like this, it helps to remember Warren Buffet’s mantra: “Be greedy when others are fearful!”

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

In a recent ABC news piece, Dr. David Swensen, manager of $34 billion Yale Endowment had this to say about Jim Cramer:

On ‘Mad Money,’ Cramer promotes a mindless short-term approach to markets by encouraging frenetic trading of individual stocks. Such a high-cost, tax-inefficient strategy almost guarantees failure.

In the same article, my view on Jim Cramer was also mentioned:

Zhuang is no fan of Cramer. Like Swensen and Ehrenberg, he argues against frequent trades and says Cramer may be influencing investors to overreact to financial news.

(For Swensen’s stellar track record, click here.)

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

Jim Cramer on Wachovia (WB)

Posted on: October 2, 2008

8/11/08 Mad Money:

I called the bottom in the financial stocks on July 15. Since that call, many of the banking stocks are up, and up big. Wachovia Bank was $8.90; now $18.60 a share. WaMu was $3; now $4.08 a share. Incredibly AIG was $20; now $24 a share. Even the troubled Fannie Mae is up from a low of $6.90 a share to $8.30 a share today.

9/5/08 Lightning Round:

I like (Wachovia) CEO Bob Steele, so this stock is a buy.

9/10/08 Lightning Round:

Consider buying Wachovia on any weakness.

9/18 Mad Money:

Investment banks, like Goldman Sachs just cannot be owned …The time has come to put the investment banks, like Goldman, on the back burner, and instead focus on the deposit banks, such as Wells Fargo, US Bancorp, Bank of America, Wachovia and JPMorgan Chase.

9/25 Mad Money:

Wachovia will also benefit from the bailout. With CEO Bob Steel’s previous government experience, he will be able to take advantage of the plan by splitting Wachovia into good and bad components and sell off the bad parts quickly to the government.

9/29/08 Mad Money:

Wachovia was toast.

Note: Jim Cramer is a vivid example of investing by a hunch, a gut feeling and hearsay. The opposite is Harvard and Yale style of investing, which is rigorous and disciplined.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

President Bush: “This sucker is going down!”

Today the Dow dropped 777 or 6.98%, making it the largest one-day point drop in history.

The ten largest one-day point drops in history of the Dow (before this one) are recorded in the table below, with subsequent one year returns calculated.

| rank | date | close | drop | % drop | 1 yr later | 1 yr return |

| 1 | 9/17/2001 | 8920.7 | -684.81 | -7.13% | 8380.18 | -6.06% |

| 2 | 4/14/2000 | 10305.77 | -617.78 | -5.66% | 10126.94 | -1.74% |

| 3 | 10/27/1997 | 7161.15 | -554.26 | -7.18% | 8432.21 | 17.75% |

| 4 | 8/31/1998 | 7539.07 | -512.61 | -6.37% | 10914.13 | 44.77% |

| 5 | 10/19/1987 | 1738.74 | -508 | -22.6% | 2137.27 | 22.92% |

| 6 | 9/15/2008 | 10917.51 | -504.48 | -4.42% | TBD | TBD |

| 7 | 9/17/2008 | 10609.66 | -449.36 | -4.06% | TBD | TBD |

| 8 | 3/12/2001 | 10208.25 | -436.37 | -4.10% | 10632.35 | 4.15% |

| 9 | 2/27/2007 | 12216.24 | -416.02 | -3.29% | 12684.92 | 3.84% |

| 10 | 7/19/2002 | 8019.26 | -390.23 | -4.64% | 9188.15 | 14.58% |

Data source: Yahoo Finance

History seems to suggest guarded optimism but I will let you decide if history is any guide for the situation today. We don’t know what the future will bring, but if we have a globablly diversified all-weather portfolio, we will be fine.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

“Ignorance is bliss” – American proverb

In 2002, Daniel Kahneman, an Israeli-American, won the Nobel Prize in Economics for his ground-breaking work in behavioral finance. During last prolonged bear market, the Israeli Pension Authority came to him with an all too common problem. Pensioners kept changing their investment allocations according to prevailing market conditions. These frequent changes not only were unhelpful for the long term, but also added costs to pension management. Kahneman gave them one simple solution: send the pensioners statements quarterly instead of monthly.

How can it help to know less about your investment performance?

I studied all seven bear markets since 1970 and calculated their peak-to-trough drawdowns (a reduction in account equity) from the perspective of four different types of investors:

- A: Investors who check their accounts intra-daily

- B: Investors who check their accounts monthly

- C: Investors who check their accounts quarterly

- D: Investors who check their accounts annually

Here are the results:

| S&P 500 | Peak to trough drawdown | ||||||

| Peak date | Peak | Trough date | Trough | A | B | C | D |

| 3/24/2000 | 1552.87 | 10/9/2002 | 768.63 | -51% | -46% | -46% | -40% |

| 7/17/1998 | 1190.58 | 10/8/1998 | 923.32 | -22% | -10% | -10% | 0% |

| 7/16/1990 | 369.78 | 10/17/1990 | 294.54 | -20% | -15% | -15% | -7% |

| 8/25/1987 | 337.89 | 12/4/1987 | 221.24 | -35% | -30% | -23% | 0% |

| 11/28/1980 | 141.96 | 8/12/1982 | 102.2 | -28% | -24% | -19% | -10% |

| 9/21/1976 | 108.72 | 3/6/1978 | 86.45 | -20% | -17% | -15% | -12% |

| 1/5/1973 | 121.74 | 10/3/1974 | 60.96 | -50% | -46% | -46% | -42% |

Two observations emerge from this study:

- Regardless of the cyclic nature of bull and bear markets, the S&P 500 index keeps marching upward. (You don’t want to stop that march!)

- The more frequently you check your accounts, the more painfully you feel (and probably will react to) a bear market.

Take the bear market in 1987 for example; the intra-day peak-to-trough drawdown was 35%. For type C investors who checked their accounts quarterly, the drawdown was only 23%. Type D investors who checked their accounts annually would not feel the pain at all since the bear market began and ended within the year. Who would be more likely to stay the course? Go figure!

The author is president of MZ Capital, a RIA serving DC/MD/VA. Get his monthly newsletter in your mailbox or get to the directory of his past articles.

Over the last 60 years, the simple average annual return of the Fama/French benchmark small-cap portfolio* was 16.3%. For the same period, the large-cap portfolio* was only 12.76%. Do you think small cap beat large cap by a wide margin? I put my mathematician’s hat on to find out.

Volatility shrinks the return difference

The small-cap portfolio return volatility for this period was 26%, and 16.4% for the large cap. Taking into account the drag to return by volatility , I calculated the geometric mean return for both portfolios. My results showed 12.9% for small cap, and 11.4% for large cap. Mathematically, the return advantage of the small-cap portfolio is significantly reduced by its volatility.

The odd favors small cap … somewhat

For most investors, long-term investing means holding a stock for three to five years. What is the odds of the small-cap portfolio beating the large-cap portfolio? Not by much.

In any given three-year period during the last 60 years, the odd of the small-cap portfolio beating the large-cap portfolio were only 51%. It increases to 58% when the investment horizon is 5 years and 72% when the investment horizon is 10 years. For most investors, the odds barely favor small-cap investing.

| Investment horizon | 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | 10 years | 20 years | 30 years |

| Odds of small cap beating large cap | 53% | 51% | 58% | 72% | 75% | 90% |

Data source: Kenneth French data library

Emotional accounting

Daniel Kahneman, the 2002 Economic Nobel laureate and the father of behavioral finance observed that the pain from a loss is twice the pleasure from a gain of the same size.

Applying his principle: I assigned one unit of positive emotion to each 1% gain and deducted two units of positive emotion to each 1% loss. So a resulted positive number represents pleasure and a negative number represents pain. The sum of monthly results over the last 60 years showed: -788 for the small-cap portfolio and -482 for the large-cap portfolio. It is clearly painful to invest in stocks, small cap stocks especially. (This also explains why people prefer to put their money in CDs.) Is the pain of small cap investing worth the gain? You decide.

There are ways to reduce the pain and enhance the gain through diversification and valuations. They are the subjects of my future newsletter, which you can subscribe here.

*Fama/French benchmark small cap portfolio contains stocks in the bottom 30% of market capitalization. Fama/French benchmark large cap portfolio contains stocks in the top 30% of market capitalization.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

Confusing volatility and risk could cost you a bundle. Let’s take a look at returns on an investment of $1000 over 50 years from 1958-2007 in five asset classes.

- Small cap value: $3,750,000

- Small cap growth: $81,200

- Large cap value: $854,000

- Large cap growth: $130,000

- CD: $13,800

Isn’t it obvious which is the best long-term investment?

Why small cap value is the best long-term investment

So you don’t have a 50-year investment horizon? Few of us do. How about a ten-year horizon? In any ten-year period from 1958 to 2007, small cap value had much better investment results than a “safe” CD. (See Table below. Green = best result in the given ten years; red = worst.)

Table: How would $1 investment become?

| 10 year periods | Small Cap Growth | Small Cap Value | Large Cap Growth | Large Cap Value | CD |

| 1958-1967 | $5.64 | $8.02 | $3.22 | $5.39 | $1.36 |

| 1968-1977 | $0.97 | $2.66 | $1.2 | $2.64 | $1.75 |

| 1978-1987 | $3.38 | $7.84 | $3.52 | $4.96 | $2.41 |

| 1988-1997 | $2.87 | $6.47 | $5.38 | $5.13 | $1.7 |

| 1998-2007 | $1.53 | $3.47 | $1.77 | $2.36 | $1.42 |

| Annual volatility | 28.23% | 24.05% | 17.67% | 18.54% | 1.7% |

Safety paradox

Even though a FDIC guaranteed CD is perceived to be safe, over time, inflation eats away at returns. For the long-term investor – and by that we mean you – small cap value is less risky.

Why do few investors put their long-term investment in small cap value? And, when the going gets rough, why do many small-cap-value investors switch their money to CDs?

Here’s why, small cap value is highly volatile (See last row of Table) and volatility makes us anxious and jumbles our judgments.

“Volatility does not measure risk.” -Warren Buffet

Volatility becomes risk only when the investor can’t stand it anymore, and abandons an otherwise safe long-term investment. Typically, volatility is highest and its impact most painful when the market reaches bottom. Not surprisingly, many investors bail out at the worst possible time.

Upon learning that he had to sail by the Sirens – the creatures whose beautiful songs could lure him to jump to his death – Odysseus asked his sailors to tie him to a mast. What mast do you tie yourself to?

Get my monthly article in your mailbox before blog posting.

Portfolio review – uncover problems, avoid losses.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

Volatility does not measure risk. The problem is that the people who have written and taught about risk do not know how to measure risk. Beta is nice because it is mathematical, it is easy to calculate and it is wrong – past volatility does not determine the risk of investing. In early 1980s, farmland that had gone for 2,000 an acre, went for $600 an acre. Beta shot up. I was apparently buying a riskier asset at $600 than at $2,000. Real estate not frequently traded. Stocks give you the ability to measure this volatility nonsense.

Because people who teach finance use the mathematics that they have learned, they translate volatility into all types of measures of risks — it’s nonsense. Risk comes from the nature of certain types of business, and from not knowing what you’re doing. If you understand the economics of the business that you’re engaged in and you trust the people you are partnering with, you’re not running significant risk.

Volatility as risk has been very useful for those who teach, never useful for us.

Get my white paper: The Informed Investor: 5 Key Concepts for Financial Success.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter