Archive for the ‘Security Selection & Market Timing’ Category

Harvard University Endowment significantly increased its holding of Market Vector Russia, iShare Mexico and iPath India in third quarter of 2009.

Harvard University Endowment significantly increased its holding of Market Vector Russia, iShare Mexico and iPath India in third quarter of 2009.

Table: Top 10 holdings in Harvard University Endowment’s public portfolio

| Rank | Names | 9/30/09 (x1000sh) | 6/30/09 (x1000sh) | Change |

| 1 | iShares E. Mkt | 10298 | 9712 | +586 |

| 2 | iShares Brazil | 3355 | 3294 | +61 |

| 3 | iShares China | 4962 | 4178 | 784 |

| 4 | iShares S. Korea | 4127 | 4349 | -222 |

| 5 | iPath India | 1882 | 1388 | +494 |

| 6 | iShares S. Africa | 1624 | 1595 | +29 |

| 7 | iShares Taiwan | 7297 | 6836 | +461 |

| 8 | Mkt vector Russia | 2596 | 882 | +1714 |

| 9 | iShares Mexico | 1639 | 570 | +1069 |

| 10 | Vanguard E. Mkt | 1568 | 1758 | -190 |

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

Warren Buffet

Being a financial advisor, I get asked to forecast the market all the time. I notice most other financial advisors would regurgitate the morning financial news and look really smart and up-to-date. I felt like I am the only one in my profession who doesn’t know what the market is going to do in the near future. So what a relief Warren Buffet threw me a life line like this one:

We have long felt that the only value of stock forecasters is to make fortune-tellers look good. Even now, (Berkshire Hathaway vice chairman) Charlie (Munger) and I continue to believe that short-term market forecasts are poison and should be kept locked up in a safe place, away from children and also from grown-ups who behave in the market like children.

I am gonna print this quote on note cards and hand it to anyone who ask me to forecast the market again.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

This is a story shared with me by Larry Swedroe …

In 1959 Harry Roberts, of the University of Chicago, had a computer generate a series of random numbers that would have a distribution matching the average weekly price change of the average stock (about 2 percent). Since the numbers were randomly generated, there was no pattern and therefore no knowledge that could be obtained by studying a chart of this nature. In order to create the illusion that his charts were those of particular stocks, Roberts placed a starting price of $40 on each chart. He then took a group of these charts to the leading technical analysts of his day. He asked for their advice on whether to buy or sell these unnamed hypothetical stocks. He told them that he did not want them to know the name of the stock since this knowledge might bias them. Each technical analyst had very strong advice on what Roberts should do but since the numbers were randomly generated the patterns were only in the minds of the observers. I am sure that you will never hear about this story from a technical analyst.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

In the mind of an investor

Posted on: August 31, 2009

Found this chart on digg.com … don’t know who to give credit to. Whoever drew this is brilliant.

Harvard University Endowment significantly increased its holding of iShare S. Korea, iShare Taiwan and iPath India in second quarter of 2009.

Table: Top 10 holdings in Harvard University Endowment’s public portfolio

| Rank | Names | 3/31/09 (x1000sh) | 6/30/09 (x1000sh) | Change |

| 1 | iShares E. Mkt | 8276 | 9712 | +1436 |

| 2 | iShares Brazil | 3170 | 3294 | +124 |

| 3 | iShares China | 3162 | 4178 | +1016 |

| 4 | iShares S. Korea | 1737 | 4349 | +2612 |

| 5 | iShares S. Africa | 1222 | 1595 | 373 |

| 6 | iShares Taiwan | 0 | 6836 | New |

| 7 | iPath India | 446 | 1388 | +942 |

| 8 | iShares Mexico | 1380 | 570 | -810 |

| 9 | Vanguard E. Mkt | 2289 | 1758 | -531 |

| 10 | Market Vectors Russia | 1762 | 882 | -880 |

| Drop | China Mobile | 376 | 459 | +83 |

| Drop | Stoneleigh Partners | 2626 | 0 | Sold Out |

Need help with investment? Call 301-452-4220.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

Investors don’t need outside help to hurt themselves. I’ve been writing about how ignoring conflict of interest, hidden fees, and not taking the necessary time to do due diligence costs investors a great deal of money. Today, I’m going to show you another way they self-inflict pain, and what to do about it.

Let’s imagine you’re in your car. Your vehicle is traveling at 60 mph. How can you, as a passenger, only be going 30 mph? You can’t. It’s an impossibility. Nevertheless, it happens in the financial world all the time.

The Harvard Management Company, which oversees the $26 billion Harvard University Endowment, recently filed a 13F-HR quarterly report with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) disclosing its portfolio of publicly traded securities as of the end of Q1 2009.

The Harvard Management Company, which oversees the $26 billion Harvard University Endowment, recently filed a 13F-HR quarterly report with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) disclosing its portfolio of publicly traded securities as of the end of Q1 2009.

Here are the most significant changes to Harvard’s portfolio:

Three dropouts

IShares MSCI UK Index Fund, iPath MSCI India Index Fund, and Western Asset Claymore Inflation-Linked Opportunities & Income Fund are no longer in the top 10. In fact, Harvard completely sold its UK index fund holding during Q1 2009.

Three additions

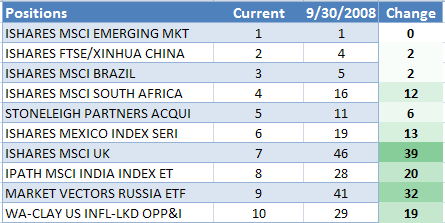

During the last quarter of 2008, the Harvard University Endowment quietly overhauled its public equity investment portfolio. By the end of the overhaul, the top 10 positions in the portfolio looked like this:

Chart credit: Paul Kedrosky

Most strikingly, seven out of the top 10 are emerging-market exchange trading funds (ETFs), with emerging-market index fund EEM and China index fund FXI the largest and second largest holdings, respectively. Year to date, EEM is up 24.55%, and FXI is up 20.85%. Comparatively, the S&P 500 is flat.

The following link contains the complete list of Chinese ADRs with fundamental scores calculated based on Piotroski’s methodology. Chinese ADRs listed in OTC markets not having financial statements are omitted. For more information about Piotroski’s methodology please read his research paper – “Value Investing: The Use of Historical Finanical Statement Information to Separate Winners from Losers.”

http://docs.google.com/Doc?id=dq62882_708t8nnsxp

Need help with investment? Call 301-452-4220.

Sign up for The Investment Fiduciary monthly newsletter.

Jim Cramer: “Watch TV, Get Rich!”

If you watch his show, you certainly would not forget the Top Ten predictions he made in January 2nd, 2008. Now that we are well into 2009, it’s about time to check the accuracy of his predictions.

On Goldman Sachs (GS)

Goldman Sachs (GS) makes more money than every other brokerage firm in New York combined and finishes the year at $300 a share. Not a prediction—an inevitability. In fact, it’s only January, and I think it’s already come true.

GS lost 59.06% last year, 22% more than the S&P 500 Index.

On oil and Transocean (RIG)

Oil goes much higher, maybe as much as $125 a barrel… We are running out of oil more quickly than people can imagine, and that means great returns for oil companies. Just buy the stock of the company you filled up at today or buy a driller (Transocean (RIG) is my favorite), then sit back and make money.

RIG lost a total of 67.64% last year, 29% more than the S&P 500 Index.

On Arabic bailout of Citigroup (C)

The Fed arranges an Arabic Heimlich maneuver on Citigroup (C), so the banking giant doesn’t choke on the worst mortgage portfolio in the country.

A David Swensen lecture on asset allocation, security selection and market timing

Posted on: February 3, 2009

David Swensen, Yale’s Chief Investment Officer and manager of the University’s endowment, discusses the tactics and tools that Yale and other endowments use to create long-term, positive investment returns. He emphasizes the importance of asset allocation and diversification and the limited effects of market timing and security selection.

Warren Buffet said: “Price is what you pay and value is what you get.”

Wall Street uses the price-to-earning ratio, or the P/E ratio in short, to determine whether one gets what one pays for when buying a stock. Is this ratio just a myth? Or is it a useful valuation measure?

To answer this question, I examined the whole stock market data for the past 50 years from 1958 to 2007. For each year, I separated stocks into three portfolios: the top 30% P/E portfolio, the middle 40% P/E portfolio and the bottom 30% P/E portfolio. (Stocks with negative earnings are all in the top 30% P/E portfolio.)

If I had invested $1 in each of the three portfolios at the beginning of 1958, by the end of 2007, the top 30% P/E portfolio would have grown to $91; the middle 40% P/E portfolio would have grown to $322 and the bottom 30% P/E portfolio would have grown to $1698! (The chart below shows the growth of $1 in the three different portfolios in logarithmic scale.)

In fact, in the past 5 decades, there was not a single decade in which the bottom 30% P/E portfolio did not outperformed the top 30% P/E portfolio. The decade spanning 1968 to 1977 was especially eventful: two global recessions, the Arab-Israeli war and the Arab oil embargo. The returns of the three portfolios in that decade are as follows:

Top 30% P/E portfolio: 31%

Middle 40% P/E portfolio: 61%

Bottom 30% P/E portfolio: 137%

It is safe to conclude that the P/E ratio is a very useful valuation measure for long-term stock investment. The lower the P/E ratio, the higher is the expected long-term return. That does not mean that low P/E stocks outperform every year though. In the last 50 years, there are 12 years in which the top 30% P/E portfolio outperformed the bottom 30% P/E portfolio. Take 2007 for example, the top 30% P/E portfolio outperformed the bottom 30% portfolio by more than 13%.

Get my white paper: The Informed Investor: 5 Key Concepts for Financial Success.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter

Academics have found out that stock returns are driven by several factors: size, valuation, fundamental, seasonal and momentum. I’ve covered the seasonal factor quite extensively in previous communications. At some point I will talk about the momentum factor as well. In this article, I will primarily talk about three very important factors: size, value and fundamental. Our investment strategy MDVFS is designed to take advantage of these three factors. These three factors are risk factors, meaning that they have their own risk/reward characteristics. By understanding these factors, you will come to grasp the risk/reward characteristics of MDVFS.

Size Factor

“Size matters” – we heard that a lot. Usually that means ” the bigger the better.” In the arena of investment however, it could mean “small is beautiful.” Based on the data in professor Kenneth French’s online library, between 1963 and 2006, small cap stocks on average outperformed large cap stocks by 3.76% a year. However, small cap stocks don’t always outperform. Out of those sample years, small caps stocks outperformed 57% of the time and large cap stocks outperformed 43% of the time. As a matter of fact, we are in a period of small cap underperforming now. In the past 12 months, small cap stocks have underperformed by about 3.61%.

Value Factor

Stocks’ valuations have very strong predictive power regarding their prospective returns as well. Though Wall Street prefers P/E as a valuation measure, academics have found P/B to have the most predictive power. Value stocks are defined to be stocks with the bottom 30% P/Bs and growth stocks are defined to be stocks with the top 30% P/Bs. Between 1963 and 2006, value stocks on average outperformed growth stocks by 6.51% a year. Value stocks don’t always outperform though. Out of the sample years, value stocks outperformed growth stocks 70% of the time and growth stocks outperformed value stocks only 30% of the time. As a matter of fact, we are not just in a period of small cap underperforming, we are also in a period of value underperforming now. In the past three months alone, value stocks have underperformed growths stocks by 7.29%.

Fundamental Factor

Fundamental factor is the strongest of all. According to professor Piotroski’s research, fundamentally strong stocks on average outperformed fundamentally weak stocks by an astonishing 18.3% a year. Despite overwhelming historical evidence, it should not be taken as axiomatic that strong stocks always outperform weak stocks. Strong stocks only outperform to the extent the market is surprised by their strengths and weak stocks only underperform to the extent the market is surprised by their weaknesses. Because large cap and domestic stocks tend to be better covered by analysts relative to small cap stocks and foreign ADRs, the fundamental factor has the best predictive power among small cap stocks and foreign ADRs.

Even the fundamental factor is not without risk. Historically, one out of seven years, fundamentally weak stocks actually outperformed fundamentally strong stocks! It is helpful to recall that during the height of the internet bubble in 98/99, people shunned solid brick and mortar stocks in favor of .com stocks without any sales. Warren Buffet was laughed at because he did not subscribe to the idea that profits don’t count any more for .com stocks. He suffered ridicules for two long years and now it’s clear to us that his patience and discipline paid off.

Conclusion

MDVFS picks fundamentally strong stocks among deep value stocks, it is therefore exposed to the value and fundamental factors by design. In portfolio composition, MDVFS assigns equal weighting to large cap stocks and small caps stocks, the resulting portfolio is also exposed to the size factor.

MDVFS is most appropriate for patient investors who do not care to follow the market, since over the long run, we almost surely will benefit from exposure to the size, value and fundamental factors. In any given moment however, these factors may not necessarily work to our favor.

Do you know that the top three one-day drops in Dow Jones happened in October? On the 19th of October 1987, Dow Jones fell nearly 23%, making the day the worst day in the US stock market history. It was followed by the 24th and 29th of October 1929, when Dow Jones fell 13.5% and 11.5% respectively, ushering in the Great Depression. These events are commonly remembered as the crash of 29 and the crash of 87.

Despite boasting the top three worst days in the market history, October is not the worst month for the stock market. That distinction belongs to September. (See Chart) In fact, summer (from June to mid October) is usually the most volatile and least productive season for stocks. Economists can not quite account for it, but this seasonality is very persistent. So much so that there is a Wall Street folklore that says “buy in November and sell in May”.

The title of my June Newsletter is “Stock Market Seasonality “. This is a good starting point to understand the “What” of this topic. In this article however, I will attempt to discuss the “Why” of stock market seasonality through the prism of Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman’s behavioral theories.

Information Accessibility

Some information is more accessible to human minds than others. For instance, visual images are more accessible to human minds than statistics. Deers kill approximately 600 times more people in the US than alligators. Yet if you ask people which of the two animals is more dangerous, nearly all would pick the alligator. Why so? Because alligators look more dangerous and the Chinese said:”An image is worth a thousand words.”

In the case of those big stock market crashes, the most accessible information to ordinary investors is the calendar information – in October they happened. The reasons, the dynamics and the consequences of the crashes are simply quite difficult to comprehend. Take the crash of 87 for example, dynamic hedging and program trading were the culprit. Because the crash was not triggered by economic fundamentals, the market recovered very quickly. Teaching of dynamic hedging belongs to PhD curriculum. It is just too difficult for ordinary investors to understand.

Anchoring

In the words of Kahneman and Tversky, “people rely on a limited number of heuristic principles which reduce the complex task of accessing probability and predicting values to simpler judgments.” One of the heuristic principles is anchoring, which is relying on the most salient or accessible information, rightly or wrongly. In the case of the crashes, the most salient and accessible information is that they both happened in October, and ordinary investors may intuitively judge that to be the plausible cause of the crashes. More thoughtful investors may suspect that both crashes happening in October is a mere coincidence, and they may mentally attempt to correct the initial intuitive judgment. According to Kahneman and Tversky, however, “the correction is likely to be insufficient, and the final judgment is likely to remain anchored on the initial intuitive impression.”

Explanation of Stock Market Seasonality

The vast majority of investors may very well anchor their understanding of the crashes on the calendar and incorrectly judge October to be the month with a very high likelihood of another crash. To hedge this imagined risk, some of them may take their money out of the market entirely in September or earlier and just wait for October to pass, causing the market to go down in summer and in particular in September. The rest who keep their money in the market would become very vigilant and may tend to interpret information more negatively than it is, causing the market to be very volatile. After October however, money would return and vigilance would be replaced gradually by holiday spirits and we get our usual year end rally.

Reference:

Daniel Kahneman’s Nobel lecture in 2002, “ Map of Bounded Rationality”

Market Sentiment and Stock Returns

Posted on: July 31, 2007

Someone asked:”Do you know of any researches/studies carried out that help predict possible upward/downward movements of equity markets?” The following is my answer.

Investors are driven to a large extent by greed and fear, and usually they are driven to the wrong directions. Warren Buffet once said:”Be fearful when everyone else is greedy; and be greedy when everyone else is fearful.” In real life, not many people can do that.

Professor Baker of Harvard and Wurgler of NYU did a study relating investor sentiment and future stock returns. They found when investors are optimistic, the subsequent one year returns are lower; when investors are pessimistic, the subsequent one year returns are higher. (See Chart) They also found small cap stocks are more influenced by investor sentiment than large cap stocks, extreme value stocks and extreme growth stocks are also more sensitive to investor sentiment. Here is their paper – https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~jwurgler/papers/wurgler_baker_investor_sentiment.pdf

Stock Market Seasonality

Posted on: June 16, 2007

Does the stock market have seasonality? Well, if you have abode by the old investment adage “buy in November and sell in May”, you would have done quite well (if you don’t count taxes and transactions costs). This is because stock gains in November through April have typically been stronger than May through October for reasons yet unknown to mankind.

The Stock Trader’s Almanac has demonstrated this by tracking what would happen to a $10,000 investment in the stocks that make up the Dow Jones industrial average. Over 56 years, this money invested in the Dow stocks in the “best six months” and then switched to fixed income in the “worst six months” grew to $544,323. But if the money invested in the Dow in the “worst six” and then switched to fixed income in the “best six” would result in a loss of $272.

Stock market seasonality is not a unique American phenomenon. A scholar at Erasmus University Rotterdam by the name of Wessel Marquering did a rigorous study of the seasonality effect of 5 major stock markets in the US, UK, Germany, Netherlands and Belgium. He found that the stocks perform better in “winter” season than in “summer” season in all 5 markets (see chart).

How can investors benefit from the seasonality effect? The short answer is “Not much.” Surely one can follow the strategy to “buy in November and sell in May”. This strategy sounds tempting in theory, but jumping in and out of stocks forces the investor to pay transaction costs and short term capital gain taxes. These costs would be more than make up for whatever benefits the strategy might bring about. Using the example referenced above at the Stock Trader’s Almanac, the total capital gain taxes adds up to about $159,000, which is much more that the $272 saved! Further more, I haven’t accounted for the transaction costs yet. Unfortunately, most investors would trade stocks and funds without much regards to the transaction and tax consequences.

Although the seasonality effect can not be exploited directly, the awareness of which could make the investors mentally prepared for the more volatile summer season. My suggestion to you is: stay put, and prepare for a bumpy ride.

Get informed about wealth building, sign up for The Investment Scientist newsletter